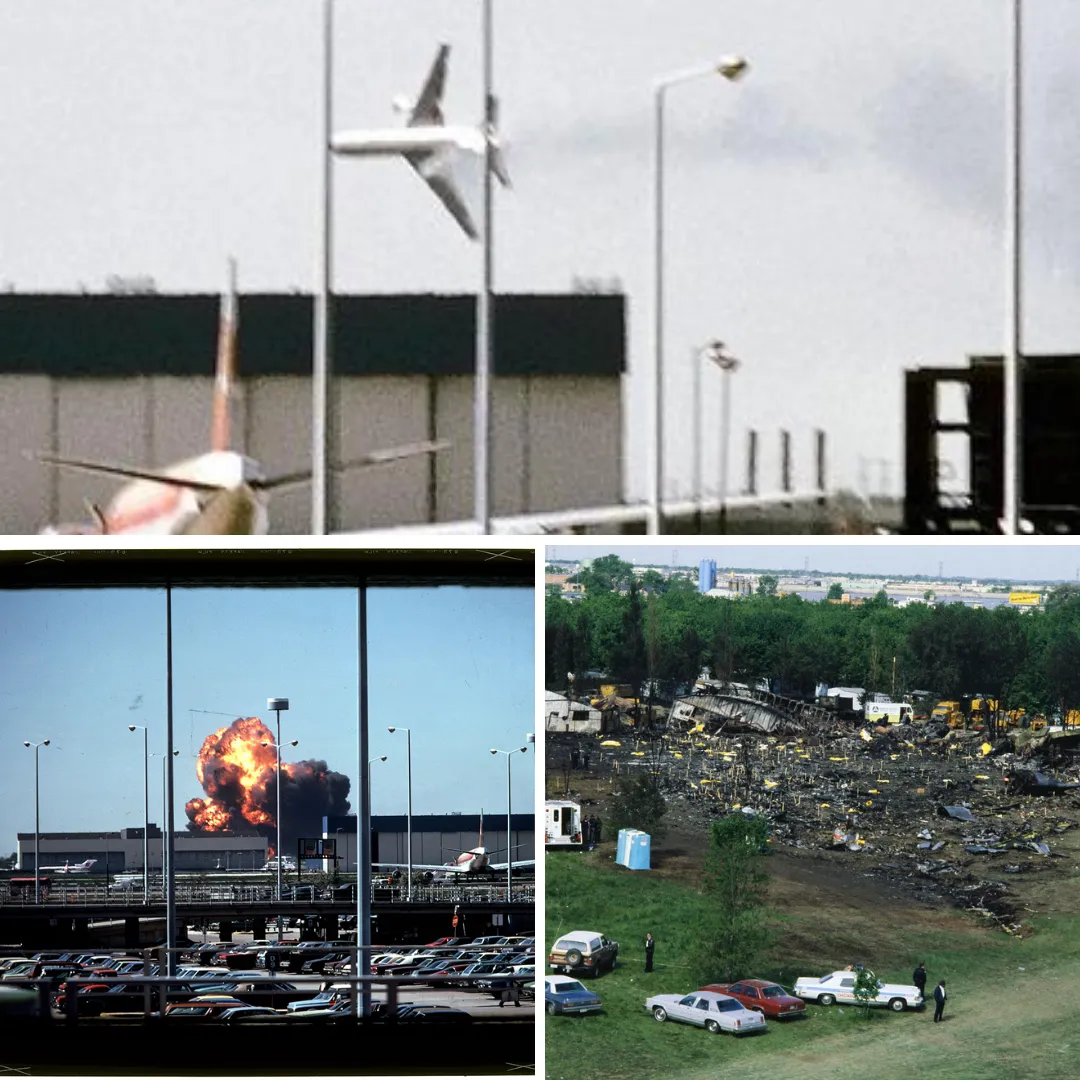

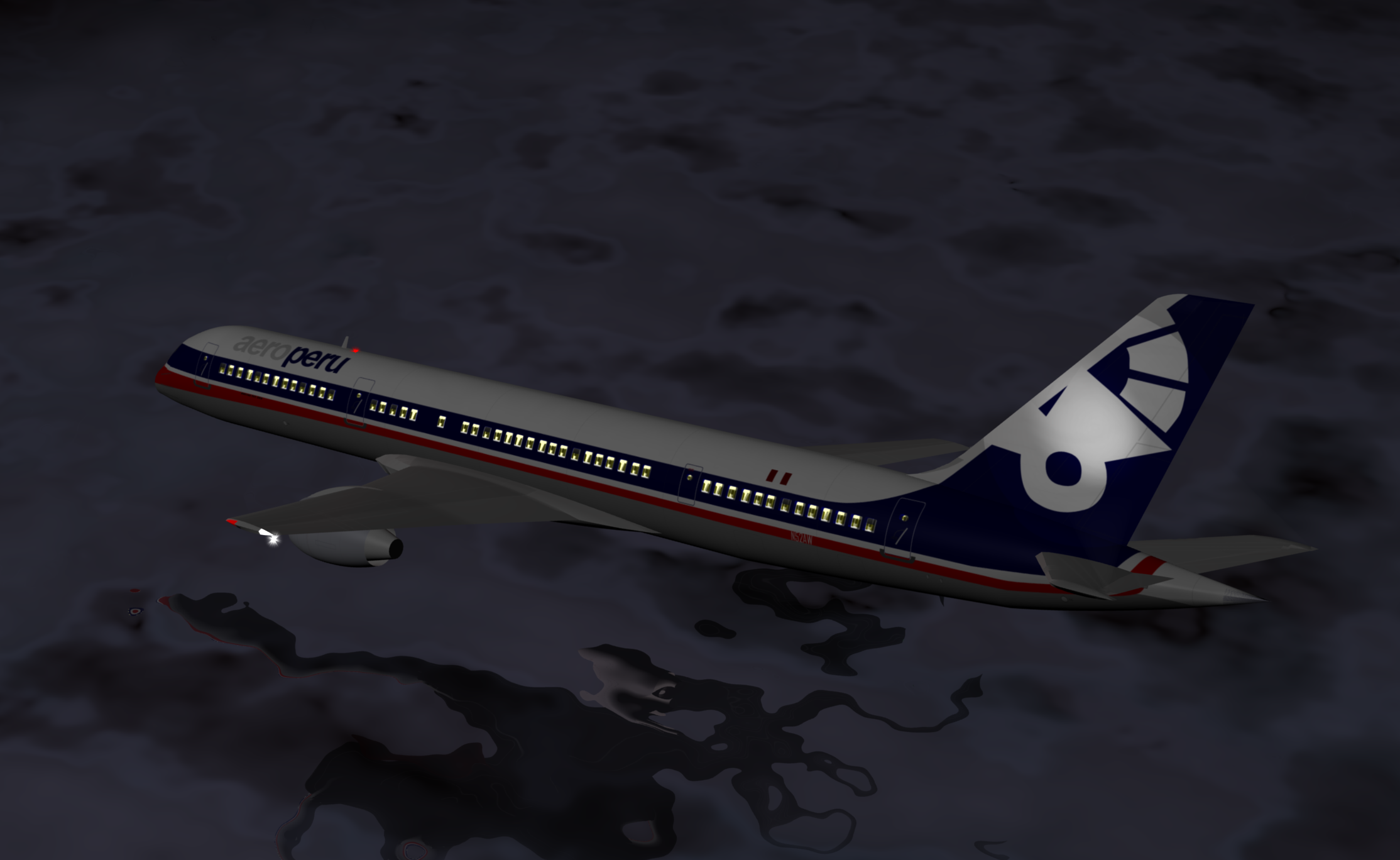

On the night of October 2, 1996, Aero Peru Flight 603 lifted off from Jorge Chávez International Airport in Lima, destined for Santiago, Chile. The McDonnell Douglas DC-9-83 was carrying 61 passengers and 9 crew members, many of them business travelers and tourists returning home.

The takeoff proceeded normally. The aircraft climbed steadily into the dark Pacific sky. But just minutes into the flight, something went wrong—terribly wrong. Inside the cockpit, the pilots found themselves in a nightmare scenario. Their instruments were lying to them.

What followed over the next 40 minutes was a harrowing and chaotic attempt by the crew to understand what was happening, all while being betrayed by the very systems they relied on to stay alive.

Unbeknownst to them, a single oversight on the ground—a maintenance worker covering the airplane’s static ports with adhesive tape for polishing and then forgetting to remove it—had triggered a sequence of confusion, misjudgment, and eventual disaster.

Captain Eric Schreiber and First Officer David Fernández were experienced and trained for emergencies, but nothing could have prepared them for what awaited them that night.

From the moment they left the runway, their flight instruments displayed conflicting, erratic, and utterly unreliable data. The airspeed indicator showed them accelerating even while they were descending.

The altimeter gave readings that didn’t match their altitude. The flight data computer activated warnings for overspeed, stall, altitude loss, and terrain proximity—all at once.

The pilots immediately informed air traffic control that they were experiencing serious navigation issues. They requested a return to Lima. From the outside, the plane looked normal—no flames, no smoke, no debris—but inside, it was chaos.

![😱B757 How It Fell On The Pacific Ocean, Aeroperu Flight 603, Lima, Peru - [Crash Animation PL603]](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/2R30Mcgrf54/maxresdefault.jpg)

As they tried to level the aircraft, they were told by ATC that their altitude appeared to be stable. The pilots, however, insisted their instruments said otherwise.

In the darkness over the Pacific Ocean, with no visual reference and an aircraft behaving unpredictably, the situation became more desperate by the minute.

Alarms blared in the cockpit. The ground proximity warning system screamed “Terrain! Pull up!” as if they were plunging toward the ocean. But when the pilots pulled back, other instruments warned they were stalling.

It was a cruel paradox—one side telling them they were falling, the other screaming they were climbing too steep.

Throughout the ordeal, the crew remained calm, professional, and determined to save the aircraft. They attempted multiple approaches, each time trying to bring the plane back safely without trusting their instruments.

But without functional pitot-static inputs, they had no reliable airspeed, altitude, or vertical speed data. In an age before advanced backup systems and synthetic vision, the pilots were flying blind.

The source of the problem—the static ports—were small holes on the aircraft’s fuselage responsible for measuring air pressure. This pressure informs key instruments like the altimeter and airspeed indicator.

During routine cleaning and polishing, a maintenance worker had covered the static ports with tape to prevent polish from clogging them. But when the cleaning was done, the tape was never removed. No one noticed. The aircraft was cleared for departure with its vital sensors blocked.

The consequences were fatal.

Over the course of 41 minutes, the pilots struggled to keep the aircraft in the air. They consulted checklists, reconfigured systems, and radioed for help. But each course correction based on faulty data only made things worse.

Flight 603 was caught in a storm of electronic lies. Every move they made—whether to ascend, descend, accelerate, or decelerate—was made in darkness and doubt.

Eventually, as they prepared for another return approach, their altitude dropped too low. With the aircraft configured in an unintentional descent, and the ocean reflecting little light in the moonless sky, they never saw what was coming.

At 1:42 AM, Aero Peru Flight 603 slammed into the Pacific Ocean at high speed, killing all 70 people on board.

The wreckage sank into the water, and for hours no one knew what had happened. When contact was lost, air traffic control believed the aircraft had made a safe emergency landing elsewhere.

Search and rescue teams began scouring the Peruvian coast. By morning, the grim reality became clear. Debris and bodies were found floating offshore. There were no survivors.

The black boxes were recovered weeks later, and when investigators heard the cockpit voice recordings, they were stunned by the professionalism and resolve of the flight crew.

Captain Schreiber and First Officer Fernández never panicked. They never gave up. Even in their final moments, as the cockpit was overwhelmed with alarms, their voices were steady, determined, focused on landing safely.

.jpg)

What the investigation revealed was both chilling and maddening. The blocked static ports had corrupted the entire flight system. The crew had done nothing wrong.

They had followed every procedure, checked every system they could. But without accurate air data, even the best-trained pilots in the world were flying in the dark.

The tape that caused the crash—ordinary metallic adhesive—was meant to be removed after cleaning. But the technician forgot. The checklist did not include a final visual inspection.

Ground supervisors missed it. Pre-flight checks didn’t detect it. One piece of tape—just a few inches wide—had doomed the flight.

The tragedy of Flight 603 triggered major changes in the aviation industry. Airlines around the world revised their maintenance procedures. Visual inspections of pitot-static ports became mandatory before flight.

Red-colored, high-visibility tape replaced the subtle metallic kind. Maintenance checklists were rewritten, retrained, and redesigned.

The manufacturer, McDonnell Douglas, issued service bulletins. The International Civil Aviation Organization recommended systemic upgrades to pre-flight and maintenance oversight.

Flight simulators added scenarios based on unreliable airspeed and static pressure errors, training new pilots to recognize and respond more effectively to such events.

But none of it could bring back the lives lost in the ocean that night.

Among the victims were businessmen, a Chilean senator, children returning from vacation, and Peruvian citizens who had boarded the aircraft expecting a safe flight.

Their families were left devastated, forced to grieve not only a horrific accident, but one that was so preventable. The pilot’s families received letters of condolence from aviation authorities across the globe, praising their courage and composure.

Captain Schreiber, who had over 20 years of flying experience, was posthumously honored in his home country. First Officer Fernández, only 28 years old, was remembered for his levelheaded thinking and teamwork during the flight’s final moments.

Together, they fought to save every soul on board until the last second. Today, Aero Peru Flight 603 stands as one of the most haunting examples of how a minor human error on the ground can lead to an irreversible catastrophe in the sky.

It is a story not of failure, but of the brutal consequence of assumption—the kind that lurks in routine. It is about how overconfidence in systems, procedures, and automation can hide fatal blind spots. And it is a story that continues to echo in every safety meeting, every hangar checklist, every pilot briefing.

Because what brought down Flight 603 was not sabotage or terrorism or mechanical failure. It was tape. A forgotten piece of tape. And the lives of 70 people vanished with it into the ocean below.