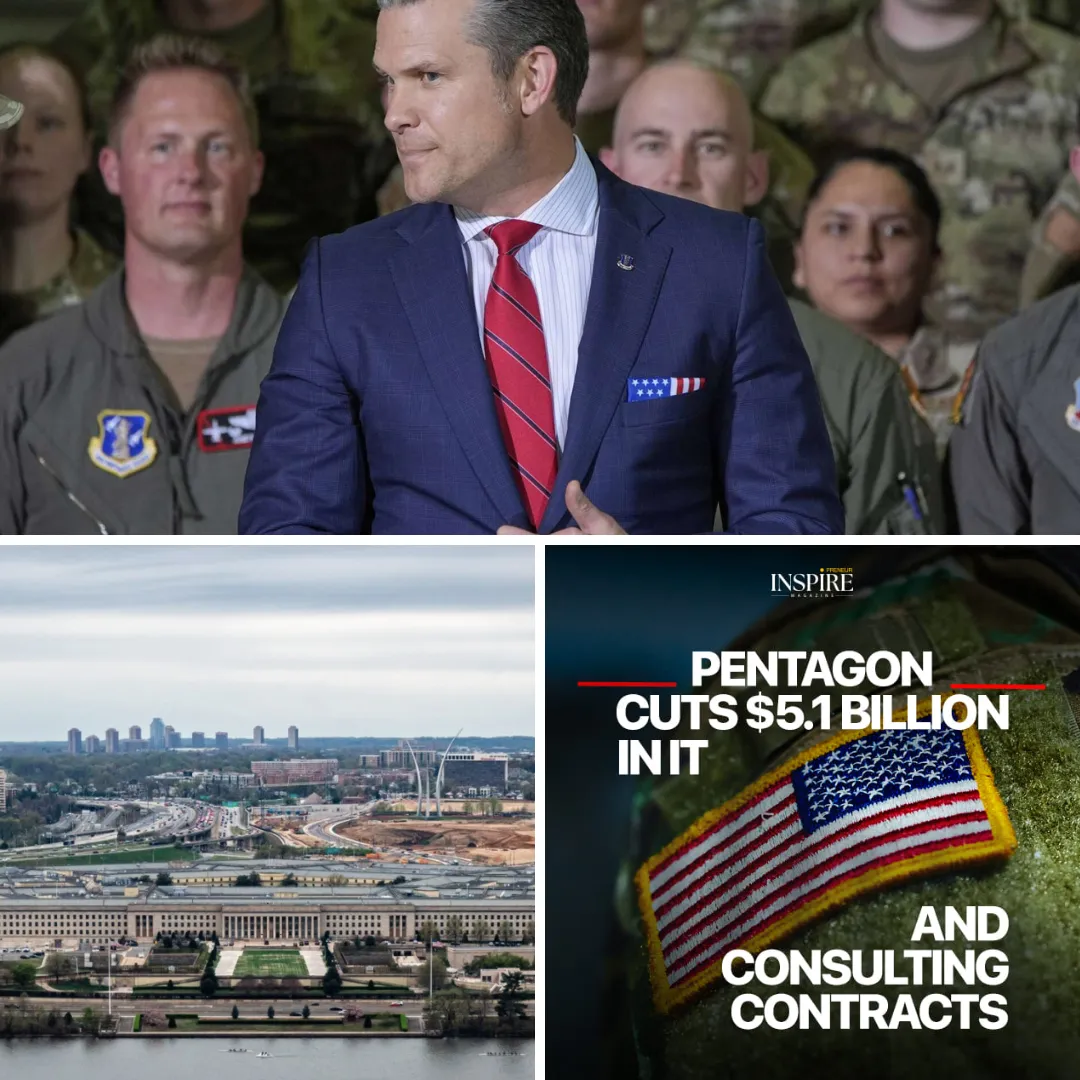

In a striking pivot that reflects the Trump administration’s new military doctrine under Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, the United States is dramatically changing its posture in Africa.

Gone is the language of long-term partnership, nation-building, and counterinsurgency rooted in good governance.

In its place now stands a far more transactional message: the time has come for America’s allies on the continent to shoulder more of the burden.

At this year’s African Lion, the largest joint military exercise conducted by U.S. Africa Command, the shift was unmistakable. The drills spanned four weeks, involving more than 40 nations, with troops conducting air, land, and sea maneuvers.

They flew drones, fired satellite-guided rockets, and practiced close-quarters battle tactics in the North African desert. But while the tactical choreography looked familiar, the language from U.S. commanders did not.

“We need to be able to get our partners to the level of independent operations,” said Gen. Michael Langley, head of U.S. Africa Command, during the closing day of the exercise.

“There needs to be some burden sharing.” Langley, who has led AFRICOM through a period of growing instability across the continent, made it clear that the Trump-Hegseth defense strategy prioritizes homeland protection and expects partners abroad to step up.

This strategic recalibration is happening as the U.S. military moves toward what Hegseth has described as a “leaner, more lethal force.”

That redefinition includes reviewing and potentially slashing military leadership posts in regions like Africa, even as geopolitical rivals such as Russia and China continue expanding their own influence.

China has launched expansive training and arms programs across the continent. Russia, through its rebranded mercenary networks, continues to embed itself in North, West, and Central Africa, often acting as a direct counterweight to U.S. presence.

In response, rather than deepening its engagement, the Pentagon under Hegseth has begun pulling back, recalibrating its message and distancing itself from the “whole of government” approach once central to U.S. military diplomacy.

The shift marks a dramatic change in tone. Just a year ago, Gen. Langley was defending the idea that force alone would not solve Africa’s layered crises.

At that time, he championed the belief that only a combination of security assistance, development aid, and good governance could stabilize fragile states and prevent violence from spreading.

He pointed to programs that tied counterterrorism efforts with environmental recovery, food security, and institutional reform — issues he believed were key to defeating insurgencies in the long term.

But now, those ideas have largely been sidelined. Under Hegseth’s leadership, the Department of Defense has made it clear that its priority is protecting U.S. interests, and that African nations must take primary responsibility for their own security.

“We have our set priorities now — protecting the homeland,” Langley said, echoing the language coming from the highest levels of the Pentagon. “We’re also looking for other countries to contribute to some of these global instability areas.”

The implications of this shift are enormous. Africa, home to some of the world’s fastest-growing insurgent groups, is also rapidly becoming a command center for international terrorism.

According to one senior defense official, both al-Qaida and the Islamic State have designated Africa as their new strategic epicenter. The official, speaking on condition of anonymity, noted that IS has already shifted its command and control structures to the continent.

These threats come at a time when many African militaries are still under-resourced, poorly trained, and unable to fully confront insurgent groups operating across vast, rugged terrain.

In places like the Sahel — a massive stretch of desert in West Africa — military juntas now rule several countries. The region has become one of the deadliest on Earth, with more than half of the world’s terrorism-related deaths in 2024 occurring there.

Somalia alone accounted for 6% of global terrorism fatalities, second only to the Sahel in Africa.

Despite these mounting threats, the U.S. has decided to limit its role. While it still maintains around 6,500 personnel on the continent, the Pentagon under Pete Hegseth is no longer emphasizing joint strategies centered on economic development, state-building, or humanitarian partnerships.

Instead, Hegseth’s Pentagon wants nations like Somalia, Niger, and Burkina Faso to prepare to fight their own battles.

“The Somali National Army is trying to find their way,” Langley acknowledged. “There are some things they still need on the battlefield to be very effective.”

Somalia, long a focal point of U.S. counterterrorism operations, continues to receive support through airstrikes and intelligence sharing. But its army, even with U.S. backing, remains too weak to hold territory cleared of militants like al-Shabab. Langley admitted that progress is uneven and fragile.

In West Africa, the situation is even bleaker. As Western nations scale down their military presence — in some cases forced out by unfriendly governments — local forces are being left exposed.

Regional militaries lack strong air support, making it nearly impossible to track or respond to insurgent movements across areas where roads are sparse and infrastructure is decaying.

Beverly Ochieng, a senior analyst at Control Risks who specializes in African security and Great Power competition, warned that the burden now falling on African states is too heavy.

“Even before Western influence began to wane in the Sahel, needed military support was limited. Threats remained active, and local militaries were left without the tools to confront them,” she said.

Langley, who is scheduled to step down from AFRICOM leadership later this year, admitted that success stories like Ivory Coast — where jihadi violence near the border has decreased thanks to integrated development and defense programs — are the exception, not the rule.

“I’ve seen progression and I’ve seen regression,” he said, signaling an understanding that the overall trajectory in many regions is worsening.

Yet the Pentagon under Pete Hegseth is still pulling back, betting that the long-standing American role as a stabilizing force in Africa can now be replaced with partnerships based more on tactical cooperation than strategic investment.

The doctrine of “burden-sharing” has become the dominant theme. Under Hegseth, the U.S. wants to train and equip allies just enough so they can carry the fight alone — without America’s constant presence.

This echoes Hegseth’s broader vision of shrinking the military bureaucracy, cutting what he sees as inefficiencies, and reallocating resources to more direct homeland defense initiatives.

But critics of the new policy argue that this shift is dangerous. By backing away from the broader mission of preventing state collapse, the U.S. risks allowing terrorist groups to gain uncontested ground.

Without diplomatic and developmental support, military action alone may simply push insurgents from one area to another, without addressing the root causes that enable them to thrive.

Furthermore, the reduced engagement sends mixed messages to African allies. While training exercises like African Lion continue, the strategic messaging from the U.S. is no longer focused on partnership, but survival.

With Chinese and Russian actors stepping into the vacuum, the long-term influence of the U.S. in Africa is at risk. Beijing continues to deepen its defense relationships with African militaries, offering training programs and infrastructure investments.

Meanwhile, Russia’s paramilitary forces, operating under different names and alliances, have rebranded themselves as reliable and authoritarian-friendly security providers.

As Pete Hegseth continues to restructure the military to reflect what he calls "real priorities," Africa is becoming a testing ground for what this new doctrine means in practice.

The old model — one of sustained engagement, interagency cooperation, and long-term investment — is being phased out. In its place is a strategy centered on speed, lethality, and disengagement.

The question now is whether this leaner, more lethal approach will actually prevent instability from spreading — or whether the U.S. will find itself returning to a continent it once helped stabilize, only to face even more dangerous threats after stepping back.

For now, African militaries are being asked to carry the burden. Whether they are ready, equipped, and willing remains uncertain. But one thing is clear: under Pete Hegseth, America’s role in Africa is changing, and the cost of that change may not be known until it's too late.