A quiet but consequential power shift is brewing across the American South. In the coming months, Republican-led state legislatures from Alabama to Texas are preparing for a coordinated redistricting campaign that could dramatically reshape the balance of power in the U.S. House of Representatives.

With the Supreme Court expected to issue a landmark decision limiting the scope of race-based protections under the Voting Rights Act of 1965, GOP lawmakers see an opportunity to redraw congressional boundaries with fewer federal restrictions — a move that could deliver the party as many as twenty new seats ahead of the 2026 midterm elections.

This potential shift is not merely procedural. It signals a transformation in how America’s political maps — and by extension, its democracy — are drawn and defended.

At the center of this unfolding battle is Louisiana v. Callais, a pivotal Supreme Court case that challenges the interpretation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act.

For decades, Section 2 has served as a cornerstone of federal oversight, preventing states from drawing districts that dilute minority voting power. Civil-rights groups have relied on it to protect majority-minority districts, particularly across the Deep South, where racial polarization in voting remains a defining feature.

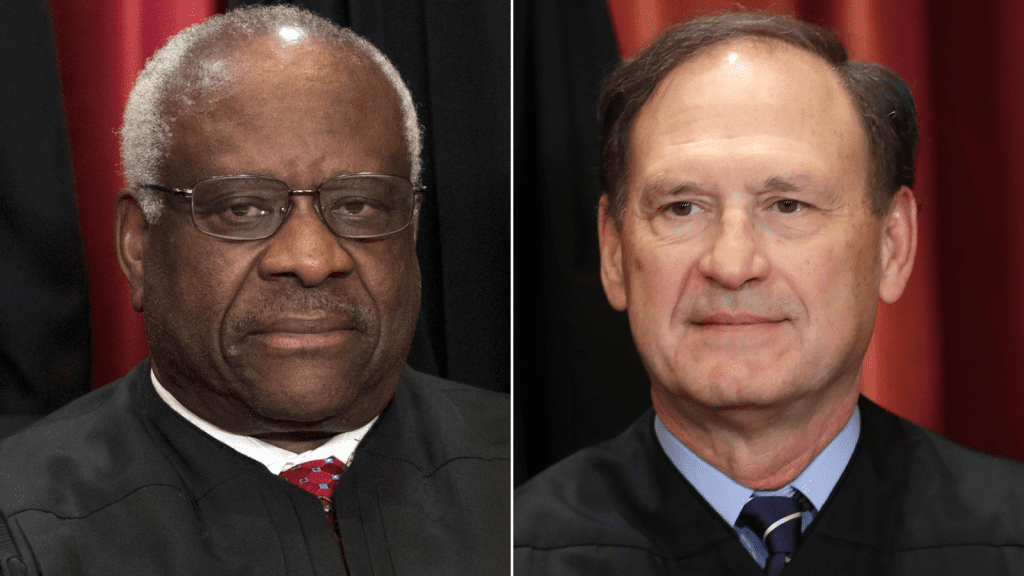

But the current conservative majority on the Court appears ready to curtail its reach. Observers note that several justices have expressed skepticism about the continued use of race as a dominant factor in redistricting, suggesting that a ruling could soon narrow the scope of permissible challenges to new maps.

Such an outcome would give Republican-controlled states unprecedented latitude to redraw their lines without facing immediate lawsuits from voting-rights advocates.

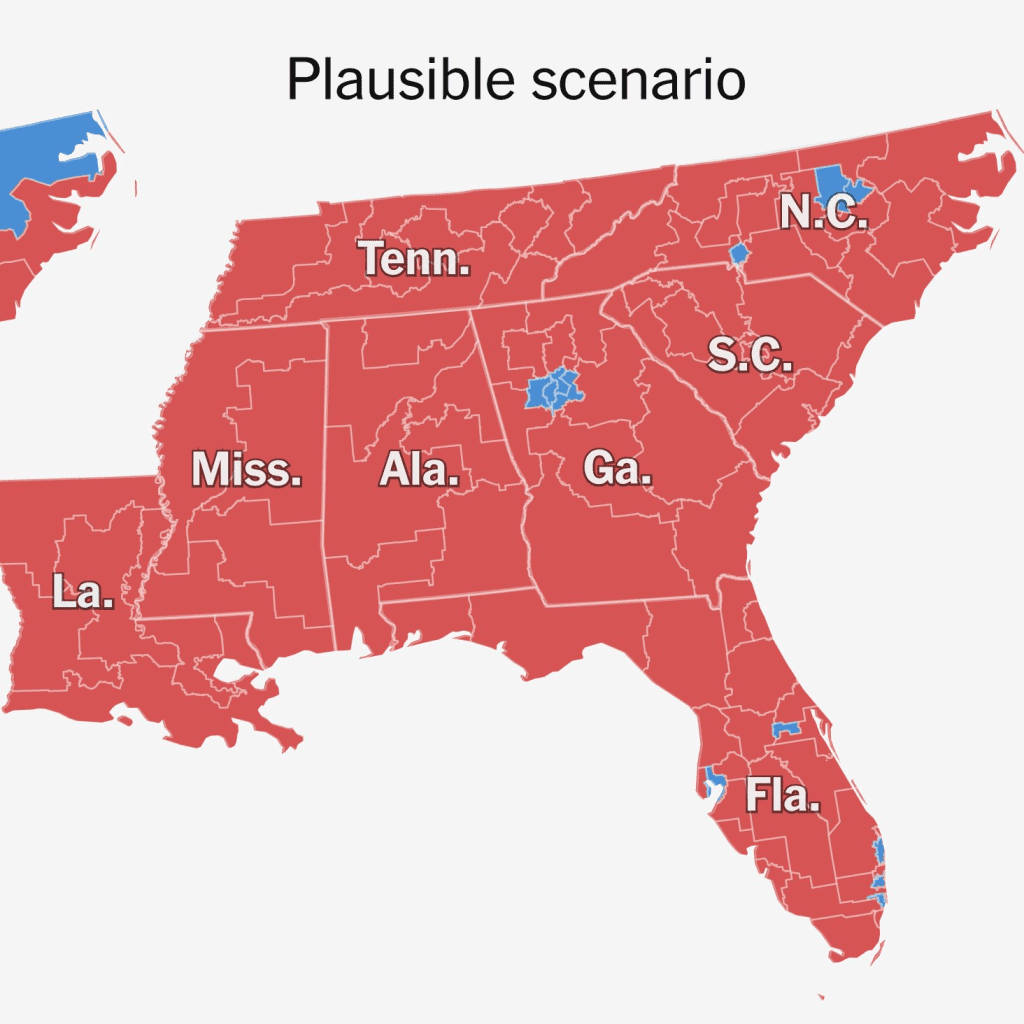

The stakes could not be higher. If the Court delivers a ruling limiting Section 2, southern states such as Georgia, Mississippi, Alabama, and Texas would be positioned to rewrite their congressional boundaries in ways that enhance Republican representation.

🚨 WOW! Southern GOP states are now preparing to REDISTRICT their Congressional maps in the event Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and conservatives at the Supreme Court END race-based VRA districts

This is HUGE!

Republicans could gain nearly 20 seats from this. Make it happen.… pic.twitter.com/BRqVq1MQvX— Eric Daugherty (@EricLDaugh) October 28, 2025

Already, some states are preparing for that possibility. In Texas, legislative aides have reportedly drafted proposals that could convert at least five competitive districts into Republican-leaning seats by consolidating urban Democratic voters and expanding suburban boundaries.

In Georgia, lawmakers are reviewing demographic data to identify regions where Black and Latino voters could be redistributed into multiple districts — a practice critics call racial “cracking.”

And in Alabama, which has been at the center of several Voting Rights Act cases, party strategists are ready to redraw boundaries that were previously struck down as racially discriminatory under federal law.

For Republicans, the opportunity is historic. The ability to conduct mid-cycle redistricting — a process usually limited to once per decade — could provide the GOP with an advantage rarely seen outside of census years.

President Donald Trump has been among those encouraging state leaders to act quickly, urging Republican governors and legislatures to “fix the maps now, not later.”

His influence remains strong in southern statehouses, where his allies dominate redistricting committees and hold key leadership posts. Many within the party view this as a chance to lock in a durable House majority ahead of 2026, especially as demographic shifts threaten to erode Republican dominance in the long term.

In practical terms, the GOP strategy revolves around converting race-based districts into ones defined primarily by partisanship. Under the current legal framework, map-makers must consider racial fairness to comply with federal law.

However, if the Supreme Court weakens Section 2, states will have greater freedom to use political criteria instead. That shift — from race to partisanship — would make it easier to draw districts that advantage Republicans without running afoul of federal courts.

Legal scholars say this approach reflects a growing trend in American redistricting: the replacement of overt racial gerrymandering with more sophisticated partisan engineering.

While race and party are often correlated in the South, the distinction could prove critical in shielding new maps from judicial review.

Democrats and civil-rights advocates have sounded alarms about the implications of this shift. They warn that weakening the Voting Rights Act would roll back decades of progress and disenfranchise millions of minority voters.

“We are witnessing the slow dismantling of the most important civil-rights law in American history,” said one senior attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

“If the Court allows states to redraw maps without regard to minority representation, we could lose a generation of political voice for communities of color.”

These advocates argue that the VRA remains necessary precisely because structural barriers to representation still exist. They cite examples like Alabama’s 2022 maps, which were found to unlawfully pack Black voters into a single district despite their forming nearly one-third of the state’s population.

Republican strategists counter that these lawsuits have gone too far, forcing states to draw districts based on racial quotas rather than genuine community representation.

They argue that the Constitution guarantees equal protection — not perpetual racial balancing — and that states should have the freedom to draw maps reflecting their political realities.

“The Voting Rights Act was meant to stop discrimination, not to mandate racial gerrymandering,” said one Republican legislator from Mississippi. “Voters should choose their representatives, not the other way around, but we can’t keep slicing the country into racial lines forever.”

For many in the GOP, this redistricting cycle represents a chance to realign the map with modern demographics, which increasingly favor Republicans in rural and exurban regions.

The political math underscores why this matters. With a narrow Republican majority in the House, even a small redistricting advantage could determine control after 2026.

Analysts estimate that if the Supreme Court weakens Section 2 and southern states follow through with aggressive map redraws, the GOP could gain up to twenty seats nationally.

That margin would not only solidify Republican control but also make it far harder for Democrats to reclaim the majority, even with favorable voter turnout.

The potential ripple effects extend beyond Congress. New district lines would also shape state legislatures and influence Senate races by changing local political dynamics. As one strategist put it, “The lines drawn in 2025 could decide who governs in 2030.”

Across state capitals, the machinery of redistricting is already in motion. In Baton Rouge, the Louisiana legislature has convened special sessions to prepare for a post-ruling environment, while in Jackson, Mississippi, lawmakers are conducting data audits to preempt future litigation.

Georgia’s redistricting committee has retained private consultants specializing in election modeling, and Texas has quietly allocated millions of dollars for mapping software and legal defense funds. These moves reflect a level of coordination that hints at a regional strategy, one driven by both legal opportunity and political urgency.

Still, the process is fraught with risk. Even if the Supreme Court limits Section 2, states could still face challenges under other constitutional provisions or state-level laws.

Additionally, public backlash could prove significant. Democrats are already framing the redistricting effort as a “power grab,” warning that it undermines fair representation.

In several states, activist groups are preparing ballot initiatives and grassroots campaigns aimed at pressuring legislatures to adopt independent redistricting commissions — a model that has gained traction in western states like Arizona and California. Whether these movements gain momentum remains uncertain, but they represent one of the few remaining checks on partisan map-making.

What makes this redistricting cycle unique is not just its scale, but its timing. Traditionally, congressional maps are redrawn once every ten years following the census.

Mid-cycle redistricting — redrawing maps before the next census — is rare and usually triggered by court orders or major demographic changes. This time, however, it is being driven by ideology.

Republicans are not waiting for population shifts; they are seizing a judicial opportunity to entrench power ahead of a crucial midterm election. For Democrats, the challenge lies in mobilizing opposition fast enough to prevent the GOP from cementing its advantage before voters have a chance to respond.

The battle over maps also exposes a deeper philosophical divide about democracy itself. To Republicans, redistricting is a legitimate exercise of state sovereignty — an extension of their electoral mandate.

To Democrats, it represents the manipulation of democratic structures to preserve minority rule. Each side frames the issue in existential terms, warning that the other’s vision threatens the republic.

The coming months will likely see a surge of lawsuits, protests, and legislative brinkmanship as both parties jockey for control over how — and by whom — the nation’s political lines are drawn.

As 2026 approaches, the redistricting efforts underway in the South could redefine not only the balance of power in Congress but the very mechanics of American representation.

If Republicans succeed in redrawing twenty or more districts in their favor, the political map of the United States could tilt decisively rightward for years to come.

If Democrats manage to block or reverse these efforts, they will preserve one of the few remaining legal barriers protecting minority voting rights. Either way, the stakes are monumental.

For now, the gears of redistricting continue to turn quietly in statehouses from Austin to Montgomery. Legal teams draft contingencies, legislators huddle behind closed doors, and advocacy groups brace for battle.

The coming Supreme Court decision may soon determine whether this next chapter of American democracy is written in red ink or remains shaded in a balance of colors.

One thing is certain: before a single ballot is cast in 2026, the fight for power will already be well underway — drawn, line by line, across the southern map of the United States.

-1750129801-q80.webp)