A new peer-reviewed study led by Stanford University has significantly revised global estimates of lives saved by COVID-19 vaccines, suggesting the actual number may be nearly 17 million fewer than previously claimed.

Published in JAMA Health Forum on Friday, the study concludes that approximately 2.5 million lives were saved worldwide between 2020 and 2024, a stark contrast to earlier figures that suggested 20 million lives were spared in the first year alone.

This revelation reignites debate around vaccine mandates, public health policy, and the long-term implications of pandemic-era decisions.

The study, authored by a team of Stanford researchers including epidemiologist Dr. John P. A. Ioannidis, draws on a more rigorous methodological approach to estimate the true life-saving impact of COVID-19 vaccinations.

One of its most eye-catching findings is the number of doses required to prevent a single death: 5,400. The data shows that of the 2.5 million lives preserved by vaccines, over 90% were among individuals aged 60 and older.

For people under the age of 30—a demographic representing nearly half of the global population—vaccines saved only about 2,000 lives during the four-year period.

Dr. Ioannidis, a leading figure in epidemiology and a frequent critic of sensationalized public health narratives, stated that while the numbers may disappoint vaccine advocates, they also serve to refute conspiracy theories that claimed vaccines were a mass killer.

“We hope people who have taken or even published extreme positions regarding COVID-19 vaccines, either favorable or unfavorable, will be willing to consider our findings with calm reflection,” Ioannidis said in an email. He added that the authors remain open to revising their estimates should more robust data become available.

This Stanford-led research lands as one of the most consequential reassessments of the COVID-19 vaccine campaign to date. It not only challenges previous studies that projected much higher life-saving impacts but also calls into question the narrative that mass vaccination of younger populations was critically necessary.

The researchers argue that the lion’s share of the benefit was concentrated among the elderly and those with significant health risks—particularly individuals not in long-term care facilities, where infection and mortality rates were highest.

The study also offers a sobering figure in terms of overall benefit: for every 900 vaccine doses administered globally, one year of human life was saved. This metric, known as “life-years preserved,” totals 14.8 million years worldwide, again with a disproportionate share among older adults.

These findings suggest that while the COVID-19 vaccination campaign was not without merit, especially for the elderly, the magnitude of its global impact has likely been overstated in earlier models.

Crucially, the study brings attention to the unintended consequences of universal vaccine mandates and aggressive public health messaging. Ioannidis noted that punitive vaccine policies aimed at younger, healthier individuals may have had the paradoxical effect of discouraging older people—those most at risk—from getting vaccinated.

“The mandates and the aggressive push to vaccinate everyone probably did not help, and the coercive, almost messianic messaging caused damage to public health with an increase in vaccine hesitancy and loss of trust in medicine and medical science,” he said.

This sentiment was echoed in a commentary accompanying the study by Dr. Monica Gandhi, an epidemiologist at the University of California, San Francisco. Gandhi emphasized that future pandemic response strategies should prioritize at-risk populations rather than push for blanket inoculation policies.

She also criticized prolonged school closures in the United States, citing the damage done to children’s education, especially among those from economically disadvantaged backgrounds. “Long-shuttered schools in the U.S. was not necessary to protect children and did harm them in terms of leading to learning loss,” she noted.

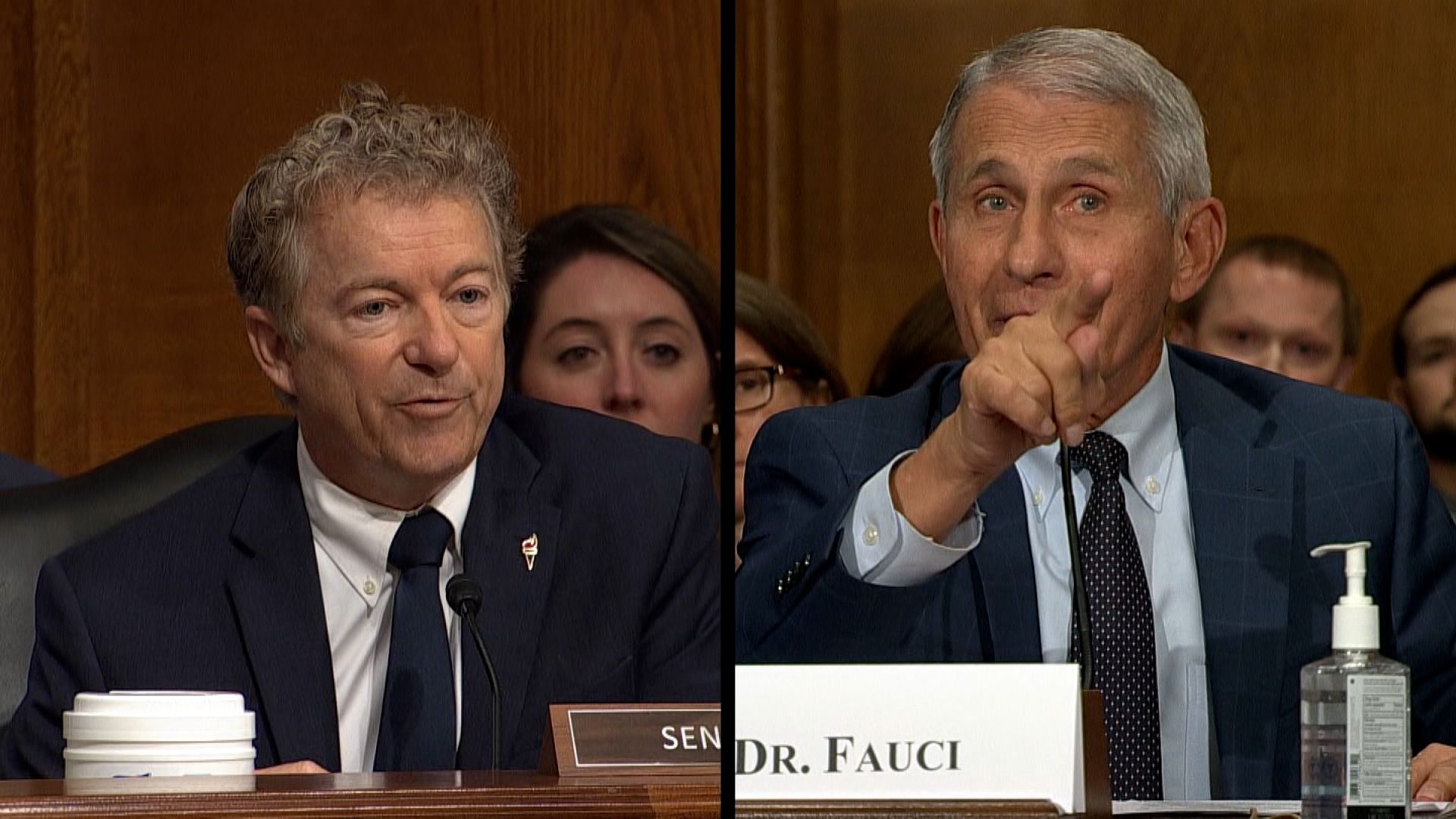

The implications of the study stretch beyond academic debate. The findings come as political tensions over pandemic response policies remain high. Republican Senator Rand Paul of Kentucky has reignited his call for a criminal investigation into Dr. Anthony Fauci, the former director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and the public face of America’s COVID-19 response.

Paul referred Fauci to the Department of Justice for a second time, alleging that the immunologist lied under oath about his knowledge and handling of gain-of-function research related to the virus's origins.

“In July 2023, I referred Dr. Anthony Fauci to the Department of Justice for lying under oath to Congress. His own emails directly contradicted his sworn testimony,” Paul said in a press release.

He further criticized the Biden administration after reports emerged suggesting the president may not have been aware of a pardon granted to Fauci, implying that such executive actions may have been handled via autopen without direct presidential review. “Fauci has been sainted by the extremist Left, but it doesn’t erase his lying before Congress,” Paul stated.

Fauci’s role in shaping U.S. policy—particularly the push for school closures, strict social distancing, and mask mandates—has long drawn scrutiny from conservatives.

Now, with academic studies like the one from Stanford casting new light on the actual efficacy of some of those measures, the backlash may grow even sharper.

According to critics like Gandhi and Ioannidis, the lessons of COVID-19 must inform a more measured and evidence-based approach to future pandemics, particularly in avoiding reactionary measures that disproportionately affect children and low-risk populations.

The study's release also reopens the broader public dialogue about trust in science, medical institutions, and public policy. While initial urgency during the pandemic justified expedited vaccine development and mass deployment, the lack of long-term randomized trials and overreliance on modeling have left many unanswered questions.

“Substantial uncertainty” surrounds even the official COVID-19 death toll, Ioannidis cautioned, with both underreporting and overreporting likely occurring in different regions and time periods.

This environment of scientific ambiguity has made it easier for misinformation to flourish and harder for genuine public health consensus to emerge. With the benefit of hindsight, studies like this one suggest that more targeted, data-driven approaches could yield better outcomes—not only in terms of lives saved but also in maintaining societal trust and cohesion during crises.

The implications for global health policy are profound. The estimated 2.5 million lives saved, while meaningful, are far fewer than the previously claimed 20 million in 2021 alone.

For younger populations, the data is even starker. Among the estimated 4 billion people under age 30, vaccines saved just 2,000 lives globally—an impact so small that it questions the rationale behind the aggressive push to vaccinate children and young adults, particularly in nations where the risk of severe outcomes was already statistically negligible.

For those aged 30 to 59, who comprise just under 3 billion people worldwide, the estimated lives saved were about 250,000. While significant, this again reinforces the central thesis of the study: that vaccine benefits were overwhelmingly skewed toward the elderly.

Consequently, any future pandemic planning should include clear risk-benefit stratification rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

In sum, the Stanford study delivers a complex message. Vaccines undeniably saved lives, but not nearly to the extent previously believed. Mandates, coercive messaging, and overreach may have undermined public trust and failed to reach the most vulnerable effectively.

The authors’ call for humility, data transparency, and targeted public health strategies offers a roadmap for a more balanced response to future crises.

As the world continues to process the consequences of the pandemic and the extraordinary measures taken to contain it, research like this is vital. It challenges assumptions, invites reassessment, and encourages future preparedness grounded not in panic but in pragmatism and precision.

The debate over COVID-19’s legacy is far from over—but perhaps now, with clearer numbers, it can be better informed.

-1750127974-q80.webp)