In May of 1990, the skies above New York City became the stage for a slow-motion disaster that took 73 lives and exposed a string of critical failures. Avianca Flight 052, a scheduled international passenger flight from Bogotá, Colombia to John F. Kennedy International Airport, was nothing extraordinary—until it wasn't.

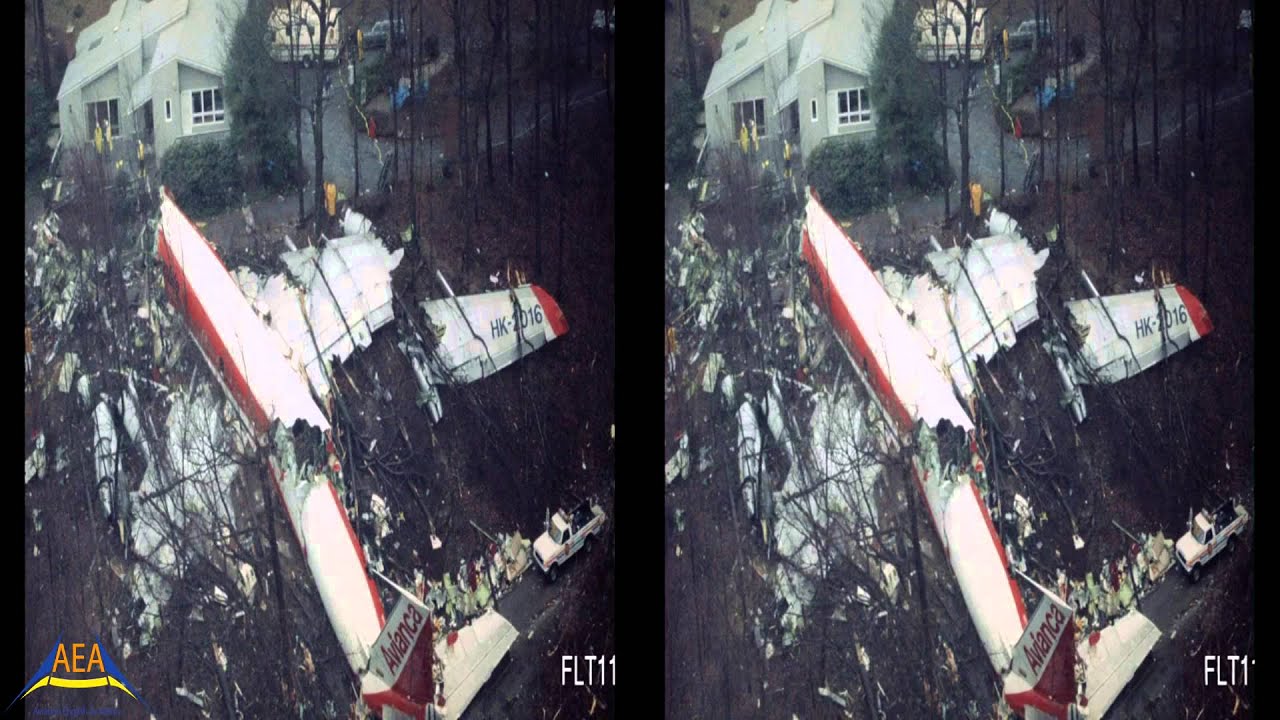

The aircraft, a weathered Boeing 707-321B registered as HK-2016, had once served Pan Am before being transferred to Avianca in 1977.

After two decades of service and over 61,000 hours in the air, it was still deemed airworthy, despite several issues, including a partially disabled autopilot system.

But nobody aboard could foresee that the aircraft's final hours would turn into a slow and desperate dance with death above a city unprepared to save them.

At the controls was Captain Laureano Caviedes Hoyos, a veteran with over 27 years at Avianca and 16,000 flying hours. He was joined by First Officer Mauricio Klotz, just 28 years old and relatively new to the Boeing 707, with only 64 flight hours on that model. Flight Engineer Moyano brought experience to the cockpit, with over 10,000 hours logged, 3,000 of those on 707s.

The crew was complemented by six flight attendants and 149 passengers, mostly Colombians and Americans, bringing the total souls aboard to 158. The aircraft departed Colombia loaded with what was considered enough fuel—35,360 kilograms—including reserves for delays and reroutes.

An additional 910 kg was added due to a last-minute change in departure runway. On paper, they were ready for the 4 hour and 40-minute flight to New York.

But the paper didn't know a storm was waiting.

After entering U.S. airspace at 17:28 Eastern Time and climbing to cruising altitude, Flight 052 encountered worsening air traffic conditions as a severe winter storm wreaked havoc along the East Coast.

Snow, wind shear, and low visibility overwhelmed control towers, leading to cascading delays and rerouted flights. By late afternoon, Kennedy Airport’s runway capacity had plummeted.

Instead of handling 80 aircraft an hour, JFK could now barely manage 33. Yet flights continued streaming in. By 16:30, 39 aircraft were in holding patterns above New York, waiting for permission to descend. Avianca 052 would be trapped among them.

First, it was held for 19 minutes off the coast of Virginia. Then another 29 minutes circling Atlantic City. Fuel was draining fast. By 20:12, after over an hour of circling, Flight 052 finally made contact with New York ARTCC.

But the delays weren’t over. They were ordered into another holding pattern near the CAMRN waypoint, where dozens of aircraft were stacked at different altitudes. The crew began to realize they were in trouble. By 20:43, First Officer Klotz radioed in that they were “running out of fuel,” but failed to declare a formal emergency.

His English, heavily accented and unsure, may have been a factor. Controllers asked for their alternate airport—Boston—but Klotz replied, “We can’t do it anymore… we’re running out of fuel.” Still, no one pushed the red button. No one said “Mayday.” The warning was lost in translation.

The lack of a formal emergency declaration led JFK controllers to treat Flight 052 like any other delayed arrival. They didn’t know the aircraft could barely hold altitude. They didn’t know it was about to die.

The pilots, meanwhile, thought they were finally getting a break when they were allowed to leave the hold and head toward Kennedy. But it was just another queue. They were instructed to perform a 360-degree turn to slot into landing order.

Time was slipping away. So was fuel. In the cockpit, the flight engineer began reading emergency checklists. Klotz nervously joked about eating hamburgers after they landed. The plane was now down to 27 minutes of fuel. Still, the controllers thought they were fine. The crew didn’t correct them.

At 21:15, they were given clearance for an ILS approach to Runway 22L. But wind shear—a sudden, violent shift in wind—disrupted their descent. The 707, flying with a disabled autopilot, was difficult to stabilize. They missed the approach. They climbed. And that was it. The engines didn’t have the fuel for another try.

In the cabin, passengers began to realize something was wrong. Children cried. Prayers filled the air. The 707 staggered through the sky in silence. One engine flamed out. Then another.

The pilots frantically called ATC: “We just lost two engines. We need priority.” But it was too late. They were told to head 15 miles east before attempting a second approach. The pilots knew they wouldn’t make it. Klotz responded, “I believe so… thank you very much.” The politeness was haunting.

By 21:34, all four engines had failed. The aircraft was now a powerless glider over suburban New York. Electrical systems went dark. The radios died. Emergency lights flickered and vanished.

The 707 plummeted silently through the night. It clipped trees and smashed into a wooded hill in Cove Neck, Long Island. The wreckage broke into three parts.

Emergency services were on the scene in minutes, climbing into the shattered fuselage to pull out survivors. But for 73 people—including all three pilots and five of the six flight attendants—it was too late. One out of nine crew members survived.

Shockingly, two of the survivors were later discovered to be drug mules, carrying cocaine-filled capsules in their stomachs—a grim reminder of the reality of international air routes from Colombia in the 1990s. But even that scandal was overshadowed by the heartbreaking failures that led to the crash.

The National Transportation Safety Board immediately launched an investigation. What they found was disturbing. Unlike U.S. airlines, Avianca lacked a flight-following system to help dispatchers track a plane’s progress and support decisions in real time.

Pilots were on their own. The cockpit crew was experienced, but their English was limited. Despite being taught emergency procedures, they never once said “Mayday” or “emergency.” FAA controllers, already overwhelmed by the storm, never understood how critical the situation was.

The NTSB ultimately concluded that the crash was caused by the flight crew’s failure to properly communicate their emergency. The captain’s weak leadership, the first officer’s poor language skills, and the lack of support from the flight engineer all contributed.

But they didn’t shoulder the blame alone. The Federal Aviation Administration also accepted partial responsibility, agreeing to pay over $200,000,000 in damages to the victims’ families.

Flight 052’s tragedy was not a sudden explosion or a midair collision. It was a quiet, creeping disaster born of delays, miscommunications, and assumptions. It was a slow-motion fall from the sky—a 77-minute descent into silence. And all it might have taken to stop it was one clear word. One declaration. One “Mayday.”

But no one said it. And 73 lives paid the price

-1751104165-q80.webp)